My Grandparents' Marriage Became a National ‘Scandal’ Due to Anti-miscegenation Laws

A special post from the L&L Archives for AAPI Heritage Month

Hello Everyone,

It’s Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month and, given the global climate of resurgent racism and right-wing nationalism, I thought this would be a good time to re-post this essay about the world my Chinese grandfather and white grandmother faced a century ago.

I first published this story when the sweeping Biden victory (by over 7M votes!) was fresh enough to reassure me we could subdue the racism and xenophobia that Trump and his MAGA zealots embody. My grandparents’ experience of bigotry still mostly seemed to belong to America’s distant past (alongside Jim Crow and Arizona’s abortion ban of 1864). Today, I fear this ugly history could well mirror our future.

Too many Asian-Americans tell themselves American racism is a White-Black matter that doesn’t apply to them. Recent immigrants, in particular, often think they can earn, educate, and excel their way to status beyond the reach of prejudice. It’s not their fault, they believe the myth of the American melting pot. But my grandparents’ experience is a reminder that this country’s racism has never been about White and Black, or education or status, either. No, American racism is about White against Other. Period.

All of us who feel Othered by the current crop of bigoted demagogues have a critical role to play this year. We must unite and vote AGAINST racist candidates, policies, and parties. We owe it to our ancestors.

My family’s tale is just one of countless true stories that remind us why.

The Wedding Party

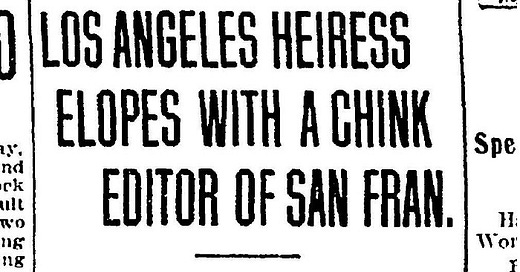

“Los Angeles Heiress Elopes With a Chink”

That headline still shocks me, though it shouldn’t. Epithets like “chink” and “Chinaman” may have fallen from favor, but as we’ve seen throughout the past decade, anti-Asian hate seethes just below America’s surface. And historically, nothing triggers racist venom like the prospect of “mongrelization.”

To prevent intermarriage between the races, America kept anti-miscegenation laws on the books for three centuries, from the 1600s until 1967. When Liu Ch’eng-yu, my Chinese grandfather, married Jennie Ella Trescott, my white American grandmother, in 1906, those laws were still in effect throughout the West. As a result, my grandparents had to cross five states before they were able to legalize their union.

None of that history is new to me. I’ve spent decades writing about my father’s parents, even basing my novel Cloud Mountain on their epic life together. But until a couple years ago, when a distant relative sent me the actual news clippings about their wedding odyssey, I’d assumed it was a private affair. What shocked me was the discovery that racist hatred had hounded my grandparents every step of the way.

According to this hard evidence, newspapers from coast to coast sent scouts to track and sensationalize this private search for a compassionate minister. Reporters must have ridden their train, because they published updates from each stop, crowing each time my grandparents were rebuffed by local authorities, and lying wildly about their identities.

The truth is that my grandparents met in San Francisco, where my grandfather attended UC Berkeley and edited a pro-democracy newspaper in Chinatown. Though descended from a long line of Imperial officials, he’d dedicated himself to modernizing China on the American model. My grandmother, daughter of wagon-train pioneers from England and Sweden, tutored him in English. When the great San Francisco earthquake struck in 1906, my grandfather saved her life. Within days, they were engaged.

They must have thought the chaos following the earthquake would shield them from public notice as they traveled east in search of a justice of the peace willing to bend the laws against miscegenation. Boy, were they wrong.

By calling my grandmother an heiress, the Denver Post fabricated her status and wealth, and by calling their odyssey an elopement, the headline implied that this Chinese alien was illicitly stealing a prized American gem. Worse, after the desperate couple finally found a cooperative minister in Evanston, Wyoming, Charleston’s News and Courier bastardized my grandfather’s name to stoke the deeper terror: “Miss Dolly Trescott, a white girl, of California, has married a Chinaman whose first name is ‘Sin.’ This should result in something original.”

The headlines might as well have read “From Migration to Mongrelization — Beware!” As one of my grandparents’ “original results,” I’m both thankful and astonished that they had the grit and commitment to persevere. But the hate didn’t stop with their wedding.

“Dislike Chinese College Graduate as Neighbor”

Back in San Francisco, the newlyweds faced another form of discrimination. Restrictive housing covenants commonly prohibited people of color, including “Celestials,” as the Chinese were called in those days, from living in “desirable” neighborhoods.

My wily grandmother had seen this coming. She’d persuaded her new husband to sign the marriage certificate as “Don Luis,” rather than Liu Ch’eng-yu. On paper, he appeared Spanish. But for the first year of their marriage, they nevertheless bounced from one apartment to another, each lease terminated when the neighbors complained.

Finally, my grandmother found a flat in Berkeley, near the college campus. Her husband, she told the landlady, was out of town. By the time this Chinese husband with the Spanish name turned up, the lease was signed and sealed and the rent paid a year in advance.

That didn’t stop the downstairs neighbors from launching a whole new Asian hate campaign, demanding, the “Chinese must go.”

My grandmother had had enough. She gave her own press interviews, denouncing her neighbors. The Berkeley Daily pronounced this “Celestial’s Wife Wrathy,” but proud Jennie defended her marriage as nobody’s business but her own. She threatened to hire a lawyer. She doubled down on the “heiress” title that the news hounds had given her during her “elopement” and outrageously claimed to be a “blue blood” with roots stretching back to the Puritans. (This strategic move was meant to deflect attention from the fact that she’d been required to surrender her U.S. citizenship in order to marry my grandfather.) She commended the local friends who supported her.

Jennie won that battle but lost the war. Though her racist neighbors initially gave up and moved away, by the following year the Liu/Luis household was living on the edge of the newly rebuilt Chinatown in San Francisco. Like so many Asians and mixed-race families in America, they were caught between cultures, not fully in either world.

In 1911, the Chinese Revolution succeeded in overthrowing the last Imperial dynasty, and my grandfather returned home to become a senator in the first Chinese Republic. Jennie emigrated with their first child in early 1912, and my father was born in Shanghai a few months later. Two more children followed.

But over the 20 years she lived in China, my grandmother never escaped the taunts of racism. The British in Shanghai banned Chinese from their parks, clubs, schools, and churches. They required “Eurasian” children like my father and his siblings to attend separate schools, and mixed-race families were discouraged from living either in the verdant and spacious neighborhoods of Shanghai’s upscale European Concessions or in the old Chinese City. Instead, they were relegated to gritty, crowded, politically turbulent districts like Hongkew — forever straddling east and west.

By the time Japan attacked China in the 1930s, my grandmother was desperate to take her four children back to the United States. My grandfather, by then an official in the Nationalist government, relented, though he stayed on. He died in China after the Communists closed the borders. Jennie never saw him or China again. As far as she was concerned, anti-Asian hate had won.

I, on the other hand, choose to believe that the “original results” of my grandparents’ union prove we all belong to the same human family and that love will have the final word.

I’m proud of my grandfather’s scholarship and idealism and of my own Chinese legacy. I’m grateful to my grandparents for their astonishing courage in standing up to anti-Asian hate at a time when American law encoded and enforced naked bigotry. And I fervently believe that we must keep telling stories like this one, not only as cautionary tales but also as profiles in courage, to celebrate and to honor.

This story was originally published on May 15, 2021, in #StopAsianHate on Medium.

More from the Chinese-American Legacy section:

A Chinese Revolutionary at UC Berkeley, 1905

When I started this newsletter, one of my intentions was to share with you bits of historical lore that I find fascinating but that may be too arcane for general readers. I’d like to return to this original plan now with one of my favorite stories from my grandfather Liu Chengyu, a scholar rev…

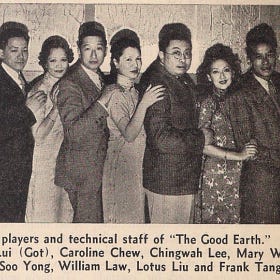

Behind the Elation Over Asian-American Oscars

Pardon me for piling on, and excuse me if you’ve already read my family story [below] about yellowface in Hollywood, but in light of last Sunday’s historic Oscars honoring so many Asian and Asian-American artists, I thought I’d re-send you the story of my father and aunt Lotus’s trip through Hollywood history. They were among the many talented actors an…

Thanks for sharing Aimee. It’s a sad reflection of our time that - even after more than a century of your grandparents marriage - we are still mired in bigotry, hate and othering. The world is in a dark place, yet I believe we will overcome because of the tenacity of people like your grandparents. Truly profiles in courage.

Your grandmother was so forthright, determined and brave and your grandfather too. Thank you for sharing their story.