One of the delights of writing for Substack is the opportunity to meet fellow writers who are on your wavelength. That’s how I got to know Katie Gee Salisbury: we’re both biracial writers of Asian descent, and we both write about Asian-American history.

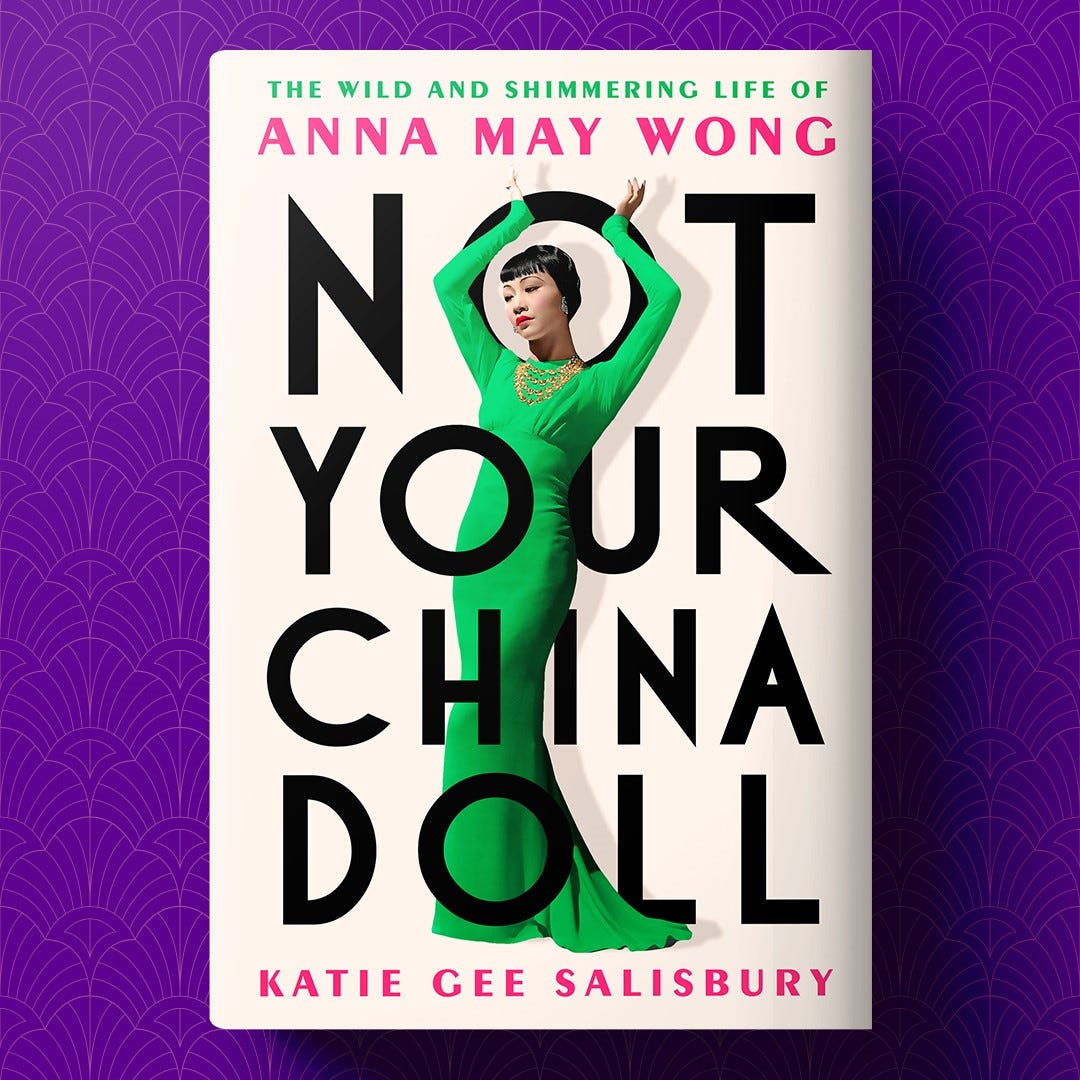

Katie, based in Brooklyn, is the author of Not Your China Doll, the forthcoming biography of Anna May Wong, and of Half-Caste Woman, her newsletter on Substack.

We’ve had so much fun getting to know each other that we thought you might like to listen in on some of our chats. In this first installment, we’re focusing on Katie’s writing journey, from initial fascination to publication of her first book, but the story of American racism, Asians in Hollywood, and Anna May Wong is also integral to this journey.

If you enjoy this conversation, please also be sure to join us virtually on Saturday, August 12 at 12PT/3ET, when we continue our discussion as part of Medium Day. Look for us on the schedule under HERITAGE AS HOOK: HOW TWO ASIAN AMERICAN WRITERS EXPLORE HISTORY ON MEDIUM. We’ll be talking about carving out a niche around cultural heritage to hook readers interested in family history and AAPI issues.

Aimee:

So Katie, you’ve got a beautiful new book coming out, and what a great title! Not Your China Doll is so right for a biography about Anna May Wong, especially today, as Asian-Americans are finally pushing back en masse against the “model minority” stereotyping of Asians. How did you get started on this project?

Katie:

The idea for Not Your China Doll really started when I first discovered who Anna May Wong was during a college internship at the Chinese American Museum of Los Angeles. Being a fifth-generation Chinese American myself, whose family largely got its start in this country in L.A.’s Chinatown, I was startled that I had never heard of her before. A Chinese American movie star who lived a hundred years ago and was internationally adored? Could it really be true? I went home and asked my mom about it and she said that Anna May Wong’s name sounded familiar but that she didn’t know much about her.

I felt it was a travesty that someone, especially an Asian American woman, who had accomplished so much in her career could be so completely forgotten. And this sense of Anna May’s story not being remembered and honored stuck with me over the next decade and beyond as I graduated from college and moved to New York to start a career in book publishing. It took some time before I felt I knew what to do with her story, but once I left the corporate world and went freelance as an editor, the newfound flexibility I gained allowed me to start researching her life.

Aimee:

I guess I’m showing my age, or maybe it’s my own family’s connection to Hollywood in the 1930s, but I’ve always thought Anna May Wong was a household name everywhere, as she was in our house. The funny thing is, I didn’t learn until recently that my father had a role in one of her pictures – Daughter of Shanghai. And I have you to thank for sharing the clips of them together! You and I have discussed the fact that a lot of false hopes were raised for Asian-American actors in Hollywood when The Good Earth was being cast – before the lead roles were all given to whites to play in yellowface. Ironically, my aunt Lotus Liu was briefly cast for the role of Lotus, which AMW declined because the character was an unsympathetic homewrecker. Had Anna May taken that role, do you think she’d have survived the cuts that eliminated all the other Asian-American leads?

Katie:

I grew up in the 1990s when there was a dearth of Asian Americans in mainstream media (outside of news anchors, which we have Connie Chung to thank for). I was so excited to see your father in Daughter of Shanghai the last time I rewatched it! I love hearing stories like your father and aunt’s, of Asian Americans in early Hollywood, because it’s a reminder that we’ve been a part of movie business all along—though perhaps not always noticed or elevated to the level of other mainstream actors, which as you mention, has a lot to do with the people who were calling the shots at major studios.

Now, about the role of Lotus in The Good Earth, the teahouse girl whom Wang Lung takes as his second wife. Anna May very publicly stated that she rejected MGM’s offer for the role because “you're asking me—with Chinese blood—to do the only unsympathetic role in a picture featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters.” As I write in my book, this was actually a sly bit of “changing the narrative” on AMW’s part. Previous biographers have never been sure whether she was indeed given the Lotus part. MGM’s casting notes suggest she was not considered favorably and that producer Albert Lewin thought she wasn’t beautiful enough to play Lotus convincingly. I found a lone clipping from Hollywood gossip columnist Lloyd Pantages that claimed AMW was actually offered the role of Cuckoo, the lady-in-waiting to Lotus, not Lotus. In this context, it makes perfect sense why AMW rejected the role—it was so miniscule—and why she spun the real chain of events to better suit her interests. MGM never said one word about her claims and, as you know, continued auditioning women for the Lotus part until they finally landed on the Austrian dancer Tilly Losch.

Aimee:

And to add insult to injury, Losch had such a thick Austrian accent that MGM hired my aunt Lotus BACK to dub her lines after jerking her out of the on-screen role. Don’t get me started!

Back to books, biography is a daunting genre, especially for a first book. How did you go about the research? And with so many thousands of images and clippings, how did you track what you wanted to include?

Katie:

It helped that when I set out to write this book I didn’t realize it was a biography! Had I known what I know now, I might have lost the courage to tackle it. However, working on other people’s books as an editor at HarperCollins and Amazon Publishing taught me a lot about storytelling. It also forced me to consider the commercial aspect of bookmaking. The point of this project was to revive Anna May Wong’s memory. It wasn’t enough just to write it; I also wanted people to read it and to tell everyone they know to read it.

One of the books I was involved with early on in my career, though somewhat peripherally as an editorial assistant, was Sam Wasson’s Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M. It’s a delicious book about the making of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. (By the way, Sam later went on to write brilliant books about Bob Fosse and the film Chinatown.) Fifth Avenue sparked something and gave me an inkling of how I could approach Anna May’s life. I decided it would have to be narrative-driven, cinematic, something engrossing enough to grab a reader’s attention and keep it.

So in that sense, I view my book as a non-traditional biography because the narrative is what drives it forward and sometimes that means glossing over certain periods of her life in a cursory way in order to serve the larger story I’m telling about her life.

As for the research, I was lucky that other biographers like Graham Russell Gao Hodges and Anthony B. Chan had already written books on Anna May and led the way in terms of what materials I should look at first. But once I got through their citations, my impulse was to do as much further research as I could. Leave no stone unturned. I started writing and researching the book full time at the start of the pandemic, so in the beginning I was simply culling as many interviews, essays, and newspaper and magazine clippings as I could from databases like Newspapers.com, the British Newspaper Archive, the Media History Digital Library, and assorted online archives. I also ordered a lot of second-hand books. Once libraries began lending again, I called up dozens of books from the Brooklyn and New York Public Libraries.

I conducted a lot of the research in tandem with each chapter as I was writing them, so I often was going through materials chronologically, i.e. when I got to a certain point in AMW’s life and had questions, I simply sought out the answers as best I could. When pandemic restrictions eventually eased up, I started making research trips to the British Film Institute in London, the Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles, the Beinecke Library at Yale, and many more.

As you mentioned, it does get to be a lot of material to keep track of! I standardized how I label and store digital files and kept the documents, scans, and images saved on my Macbook Air (though I made sure to back up to an external hard drive often). I also printed out almost every newspaper or magazine clipping and filed them into physical folders labeled by year, film, or other topic. I find it’s much easier for me to flip through physical pages to find something I’m looking for (not all documents have searchable text) and it also helped me review specific periods of her career in full as I was preparing to write about them.

Aimee:

Your publisher is Dutton. Congratulations! Tell us about the process of pitching and selling this book. What was your hook?

Katie:

I did some initial research in 2018, and in the spring of 2019 I put together a basic book proposal, without a sample chapter, that I shopped around to a handful of agents. Some of them were agents I had known or worked with while I was an in-house editor and a couple were agents who had reached out to me after I’d published various articles. I had conversations with several agents. I decided to move forward with Alia Hanna Habib at The Gernert Company because I felt she really got what the book was about. Some agents had felt there was room to have other historical personalities share equal weight with AMW in the book, but Alia pushed me to make AMW the sole focus—and that felt right to me.

Of course, I had to write a sample chapter before we could pitch the book to publishers. This was scary and anxiety-inducing. It meant I now had to figure out how to write the book! Or at least a chapter. I dragged my feet on it for a year but finally bit the bullet over the Christmas holiday. By the new year, I had a sample chapter and my agent went out with the proposal in February 2020. The hook was essentially the untold story of Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star.

I took meetings with four publishers, just weeks before the COVID-19 lockdown—my agent and I religiously washed our hands before and after every meeting. In the end, an editor at Dutton made a pre-emptive offer for the book and I accepted!

Aimee:

Your pub date is March 2024, right? How are you prepping for the release?

Katie:

Since turning in the final final manuscript in March, I’ve been trying to ease back into normal life. The thing that no one tells you is how physically arduous writing a book is! I have to be honest, during the last six months of the race to finish, my health really suffered. So in recent months I’ve been going to the gym and sleeping more. I’m also reading books for pleasure again, which is such a treat.

As for book promotion, I’ve got a million ideas written up in a Google doc. A lot of the prep is simply telling people about the book and coordinating with my publisher’s marketing/publicity team. I also have a number of ideas for op-eds I’d like to write and pitch closer to publication as well as some fun giveaways to encourage pre-orders. Another author friend recently advised me to start thinking about my event outfits, so there’s that too!

I loved this interview. Can't wait to read the book!

Fascinating - will definitely read!