On Writing 'The River's Daughter'

A conversation with debut author Bridget Crocker about inspiration, perspiration, salvation and the grace of nature and memoir writing

I had to do the emotional recovery work to be able to access forgiveness and develop empathy and then go back and infuse that into the writing.

Hello Loreates!

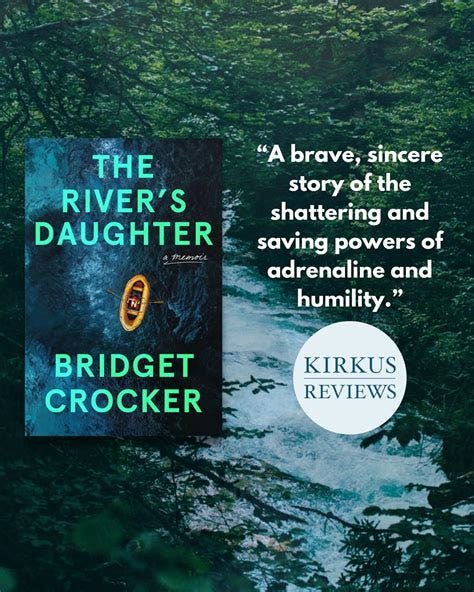

It gives me enormous pleasure to share with you my conversation with , author of the dazzling debut memoir The River’s Daughter, out next week from Spiegel & Grau.

Like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, Bridget’s memoir highlights the healing, if brutal power of nature, but I am not kidding even a little when I say that Bridget’s is by far the superior literary work. It’s more beautifully crafted. It’s braver. And it resounds with a depth of wisdom and grace that I’ve rarely found in any memoir, including Strayed’s.

The River’s Daughter chronicles the many times rivers saved Bridget from childhood poverty, trauma, physical and sexual violence, and how she found strength and purpose in her relationship with some of the most dangerous currents in the world as she became a world-class whitewater rafting guide. This is a gripping story of survival and adventure, courage and wonder. I truly could not put it down, and I was overjoyed when Bridget agreed to tell me about her process in writing it.

Just so’s you know, as my former program director used to say, here’s Bridget’s official bio:

- is the author of the memoir, The River's Daughter (available June 3, 2025). A leading whitewater explorer, Crocker has guided expeditions down many of the world's greatest river canyons in Zambia, Ethiopia, the Philippines, Peru, Chile, Costa Rica, India and the western United States. Her work has been featured in Outside, Westways, Men's Journal, and National Geographic Adventure magazines among others, and she is a contributor at Patagonia, Lonely Planet Guidebooks, and The Best Women's Travel Writing. She lives with her family in Malibu, California. Visit her at www.bridgetcrocker.com or follow @bridgetcrocker .

Also be sure to tune in to Substack for my LIVE conversation with Bridget on Wednesday, June 11, at 12pmPT / 3pmET. Details below!

Thanks so much for being here! MFA Lore is a reader-supported publication that offers the essence of an MFA in creative writing, minus the tuition! For full access to all posts and bimonthly Loreate Zoom Gatherings, as well as the special MFA Lore Exercise at the end of this post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Would you like an MFA-level response to your work?

Becoming a Premium Member of the MFA Lore community will entitle you to Aimee’s written feedback on your query and up to 5 pages (1250 words) of one project. Your “Take 5 Packet Letter” will highlight both the Strengths and the Opportunities in your work, helping you determine whether it’s time to “press send” to agents or reorient your revision. Price will go up next month, so subscribe or upgrade today!

Meet River Whisperer, Bridget Crocker

The themes of rivers saving and raising me became obvious. I didn’t really work to create it, it was already there.

Aimee: The voice of the river and the profound sense that the river saved/raised you–these are central to The River’s Daughter. When in the writing process did you realize they would be critical– and literal (not just thematic) –elements of your story?

Bridget: Long before I began writing the first draft of The River’s Daughter, I was sharing the story of how I communicate with rivers. Initially, fellow guides would ask about a particularly good line through a rapid, and how I came up with it, and I’d say the river told me where to go. When I taught guide schools, how to communicate with the river was something I shared with students. That teaching naturally flowed into the writing of the book because it’s inextricable from my story and knowledge of rivers. Structurally, I focused the narrative on scenes with rivers, beginning with my childhood, and as these scenes began to flow into each other, the themes of rivers saving and raising me became obvious. I didn’t really work to create it, it was already there.

Aimee: So powerful! And so fortunate for you as a writer to have that clarity and vital through-line up front. There are many other issues that play into your story – domestic and sexual violence, betrayal, all the isms from sexism to colonialism– in addition to the unpredictable power of nature, yet you chose a simple structure, with scenes strung like beads on a chronological chain, and you didn’t move back and forth in time until the very end. Did you experiment with different structures, or was this the pattern from the gitgo?

Bridget: I completely restructured the timeline four times. Initially, I was doing a back-and-forth timeline between the childhood and guiding chapters. The primary reason for this was fear: I was afraid that having two sexual assault chapters–”Nothin’ Left to Lose” and “Lifejackets, Condoms and Seatbelts”–appear in the story back-to-back would be too much for readers to endure. Inevitably, the structure fell apart with the split timeline, as there were too many characters and worlds to track and an exhausting amount of exposition. Finally, someone in my writing group convinced me that since it was already a complicated story (for all the reasons you cited), it needed to be told simply for readers to be able to follow it. I really agonized over it, but again, my writing group told me to trust that readers would be able to manage it, after all, I had lived through it and survived, surely they could survive reading it. That was a huge trust moment for me, to reveal the entire emotional weight of how it felt to live through those events in rapid succession, and to trust that readers wouldn’t abandon the story in sharing the heaviness of it.

Aimee: God bless writing groups! How could we survive without them?

The core of the memoir ends when you’re still in your early 20s, making this a coming-of-age story. That surprised me a little as a reader! How did you decide on this time frame?

Bridget: When I first set out to write it, I included sections that went through to my thirties, but there was way too much material to cover in one memoir, so I focused on the early years. The good news is that in wandering around in the vast wilderness of material, I was able to better map out the timeline and I have the next two books partially written.

Aimee: Lucky you! That reminds me that F. Scott Fitzgerald turned the cuts from his novels into short stories. I’ve only managed that a few times, but it’s a good practice to give yourself plenty of launchpads for new work!

And the distillation that results in this book is extraordinary. Each of the scenic “beads” you string on your story’s chain is vivid and cohesive, and you boldly leap from one to the next with minimal transition or exposition as filler. How did you decide which scenes would serve as beads? Did you have to cut a lot of transitional material before finding the courage to jump over time gaps?

Bridget: That happened organically as a result of tightly focusing the scenes on my relationship with rivers. It is primarily a story of that relationship, and so all the characters and history are there to support that arc and communicate how my relationship with rivers developed.

Aimee: Memoirists often agonize over the issue of memory gaps and uncertain details. In your author’s note you acknowledge taking some liberties, including composite characters and shifting or recreating dialogue. How did you decide what was okay to change and what aspects of scene-setting had to be totally factual?

Bridget: Years ago, Isabel Allende said in a Writer’s Digest interview that, “There’s an element of fiction in everything you remember. Imagination and memory are almost the same processes.” Although I kept track of events as they happened in my journals, there were scenes where I didn’t have a written record, but they were seared in my mind. I chose to trust my memory, which was an act of empowerment itself since I grew up in a family culture of denial and gaslighting and being told repeatedly that my memory of the events that shaped me wasn’t factual. I created composite characters for some of the background characters–the dialogue was accurate in these places, but it didn’t serve the story to have every guide or client that was on the trip developed so they could say one line, so I’d combine the characters in places like that for greater dexterity in scenes.

Aimee: Well done! A good chunk of this story takes place in Zambia and Zimbabwe, where you wrangle with some very ugly -isms– colonialism, racism, and sexism. I was amazed at the breadth of historical and political context that you were able to telescope into your personal encounters. Did you write these sections purely from memory, or did you have to research the broader context before you could make sense of your own experience?

Bridget: By trade, I am a guide and a travel writer. Part of my job is to share information about places through which I’m traveling and guiding others, both on the ground and on the page. I remember a lot about the historical and political situation in Zambia and Zimbabwe because I made it a point to learn it while I was there, which meant reading and asking a lot of questions and taking notes in my journal. I also did substantial additional research as part of the fact checking process, to make sure I had it right.

Aimee: Another major stopper for many memoirists is family reaction. You write about your parents with great empathy, but you definitely show them, warts and all. We ultimately get your father’s perspective – and your extraordinary emotional journey with him from start to finish. Your mother is a more complicated character in the story, and it’s not clear how she’s reacted to the book. Did you worry about her response as you were writing?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Aimee Liu's MFA Lore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.