The Lure of the Andaman Islands

Why this unforgettable place insisted I set my novel there*

The core idea for my novel Glorious Boy came to me in this dream:

On a tropical island during an emergency evacuation, a young girl hides in a dense rainforest with a small, mute white boy in her care. The girl, local to this island, knows the boy’s parents will not take her with them. She’s hiding out of equal parts jealousy and spite. Only when the noise outside dies down does she emerge with the child to find streets abandoned, spectral plumes of smoke rising in the distance, and the little boy’s parents gone. Only then does the girl realize the terrible gravity of what she has done.

The dream was set in no specific era or locale. The evacuation was generic, likely inspired by news reports of expats fleeing from West African war zones — this was 2003. Yet in my mind, the story took place in the Andaman Islands.

A different writer might make it up, but I needed to base my fictional evacuation on real unrest. I’d have to visit the islands in person to decide if there was any actual “there” there for me.

I’d first heard about the Andamans six years earlier during an encounter with an anthropologist’s wife. I’d been reading from my novel Cloud Mountain at Diesel Books in Oakland. Two women from the neighborhood sat in the front row. Only one of them was interested in my talk, which focused on my family’s history in China. The other, the anthropologist’s wife, had merely tagged along. When I mentioned that I planned to set my next novel in India, however, she piped up.

Sharon and her husband had just returned from a remote archipelago in the Bay of Bengal that until recently had been closed to foreigners. If I was interested in India, she insisted, I must visit the Andaman Islands.

What made the Andamans so fascinating, she said, was the unique blend of cultures that had evolved there. Most of the interior was still primeval forest, home to indigenous tribes whose ancestors first arrived from Africa more than 60,000 years ago. Some, even today, had no contact with the outside world. The islands’ modern settlements were sparse and coastal, offshoots of the capital Port Blair, which was founded as a penal colony for Indian freedom fighters during the British Raj.

The Andamans lie several hundred miles off the coast of India, and few convicts ever escaped. Instead, united by the common goal of ending British rule, the Indian and Burmese prisoners gradually established their own “local-born” identity. Those who stayed on after Independence in 1947 rejected the caste and religious divisions that dominated life in the rest of India. Ironically, the former penal colony became a zone of cultural harmony.

Despite Sharon’s exhortations, the Andamans slipped to the back of my mind, where they remained on a creative simmer until that dream in 2003 turned up the heat. By then the Indian government seemed to have shifted policy, from prohibiting foreigners to enticing them as tourists to this “natural paradise.” Travel websites featured photos of empty white beaches snaking between turquoise coral reefs and heavily canopied rain forest. In aerial shots the islands looked like jade buttons embedded in aquamarine.

The history of the various Andamanese populations was now well documented online. One set of images dated from the late 1800s, when British officials imprisoned native Andamanese in a “home” where they could be measured and inspected like specimens. The indigenous islanders in these old photographs had scarified skin, and their clothing was little more than strings and woven bands. Their expressions bespoke defiance, contempt, and pride.

Later pictures recorded the relocation of more than 4,000 Hindu refugees to Port Blair after the partition of Bengal into Pakistani and Indian territories in the 1950s and another major influx in the 1970s after the Bangladesh War of Independence. By this time, most of the indigenous population had been wiped out by disease and encroachment by Indian settlers and loggers on their territory. My initial impressions of the Andamans were growing darker. Still, I couldn’t quite locate the story from my dream within the history I was absorbing.

Then I read Daniel Mason’s 2008 novel A Far Country, set in an unnamed third-world state cursed by drought and inequity. I tried to follow Mason’s lead and invent an island loosely based on the Andamans, with a fictional uprising, but the dream story refused to take root in imaginary earth. There had been no modern uprisings in the Andamans that I could find, and when I tried to fabricate one, my narrative collapsed for lack of specificity and cultural depth.

A different writer might make it up, but I needed to base my fictional evacuation on real unrest. I’d have to visit the islands in person to decide if there was any actual “there” there for me. When I finally made that trip, late in 2010, what I found catapulted my own momentum forward even as it propelled my fiction half a century backward.

I sensed this shift as soon as I set foot on Ross Island. A short, muggy ferry ride across the harbor from the contemporary “mainland” of Port Blair, this open-air museum was like an organic time machine. Home to the Andamans’ British officials until World War II, the 150-acre cantonment now consisted of ruins interwoven with the massive roots of soaring ficus trees.

These giant tentacles were relentless, twisting through, around, and over the battered remnants of Ross’s colonial architecture — the skeleton of the old Christ Church, the rubble of British troop barracks, the shell of the cantonment swimming pool, the imperious stone and iron gates opening onto the forecourt of a hilltop aerie where the Chief Commissioner’s headquarters once stood.

It was as if nature were intent on devouring all evidence of the former colonizers. I was dumbstruck by this indelible fusion of history, growth, and decay, all bathed in green shadow and sweltering heat.

Only the bungalow that once served as a bakery had been restored. Inside the relative cool of this shelter, a photographic exhibit told the story of Ross Island’s colonial heyday as “the Paris of the East.”

Over in Port Blair proper, the Indian rebels had been imprisoned in the notoriously brutal Cellular Jail, but here on Ross, croissants were baked fresh each morning, and tipsy couples danced the foxtrot at the European Club. There were Victorian bungalows with gingerbread trim, a hospital wrapped in a wide veranda, a multicolored Hindu temple for Indian soldiers and servants.

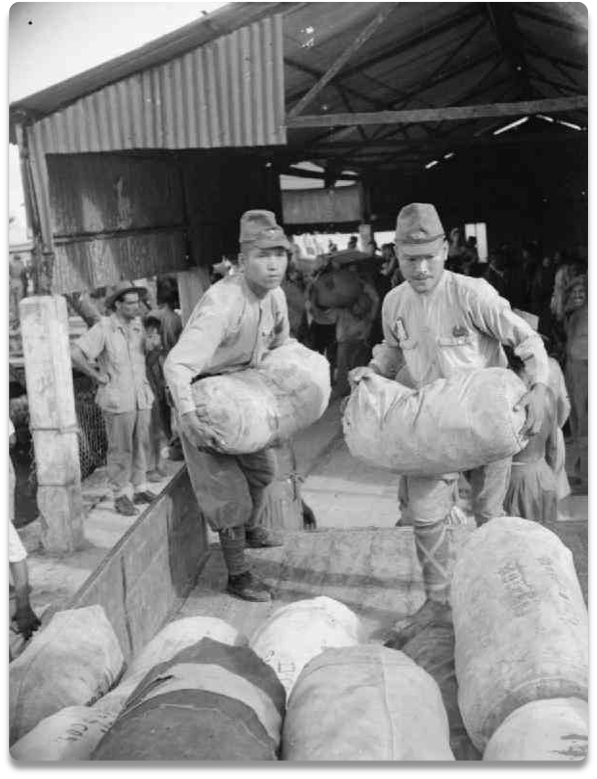

Shaky newsreel footage from the 1930s showed soldiers drilling on the parade ground and Victorian ladies in white hats tittering from a rickshaw “buggy” that required four convicts to push-pull it up Ross Island’s steep central ridge. Cantonment life looked like a lark until you factored in the 90-degree heat and humidity and the months-long deluge of the annual monsoons. Also, while the lines might have blurred between Indians and Burmese, the divide between colonial subjects and masters during the Raj was absolute.

The dream was set in no specific era or locale. Yet in my mind, the story took place in the Andaman Islands.

The myth of the Paris of the East collapsed on June 25th, 1941, when an 8.0 earthquake struck, followed by a tsunami. Overnight, Ross Island was abandoned, the administration decamping across the harbor.

Just eight months after that, the Japanese invaded. They would occupy Port Blair for the duration of World War II. That explained the blood-red bunkers I’d noticed around the island’s perimeter. But what had become of the Indian freedom fighters during occupation? When did the British evacuate? And how did the indigenous Andamanese fare?

I left Ross Island with an armload of rare books and pamphlets that answered these questions. Penned by local authors, they described what it had been like to grow up in the Andamans before the war, the former convicts’ uneasy relations with the forest tribes, and the warm welcome the Indians in Port Blair initially gave the Japanese, believing them to be their “liberators” from the British.

The evacuation of Europeans from the port had been late and rushed, and a second expected ship was torpedoed, leaving key officials and Indian troops with no choice but to surrender. In short order, the Japanese arranged public executions of unruly locals. The former assistant commissioner was falsely accused of spying, then summarily beheaded. Later, British Special Operations sent reconnaissance missions back to the islands, tapping the chief of one of the forest tribes to actually spy for the Allies.

This wealth of story material ignited my imagination. Suddenly the girl of my dreams was the daughter of a freedom fighter who’d died in the 1941 earthquake. Her strangely mute charge now emerged as the young son of Port Blair’s Civil Surgeon and his American wife, an aspiring anthropologist (tip of the hat to Sharon) intent on studying the forest tribes.

The little boy’s inexplicable silence was the source of secret jealousies and tensions that would pitch them all into unknown territory on March 13th, 1942, the day Port Blair really was evacuated. And those massive tree roots I’d seen on Ross Island suggested the perfect place for two errant children to hide.

* The original version of this essay was originally published in Literary Hub .

Glorious Boy is available from Red Hen Press.

Subscribers, remember, you control the emails I send you!

Aimee Liu’s Legacy & Lore now offers 2 Sections:

1) Chinese-American Legacy and

2) MFA Lore.

To control which sections you receive as emails, please go to your profile settings, click Subscriptions and choose Aimee Liu’s Legacy & Lore. Then, under Notifications select which sections you wish to receive (green) and which you don’t (gray).

More directions HERE.

I’ve enjoyed reading Glorious Boy and was glad to learn the backstory!