When Anti-Miscegenation Laws Reflected the Worst Kind of Bigotry

My grandparents’ marriage became a national ‘scandal’ because of anti-Asian hate

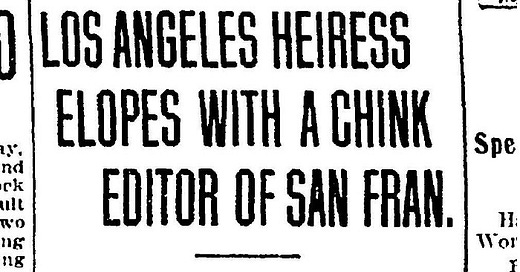

“Los Angeles Heiress Elopes With a Chink”

That headline still shocks me. It shouldn’t. Epithets like “chink” and “Chinaman” may have fallen from favor, but as we’ve seen throughout the past year, anti-Asian hate seethes just below America’s surface. And historically, nothing triggers racist venom like the prospect of “mongrelization.” To prevent intermarriage between the races, America kept anti-miscegenation laws on the books for three centuries, from the 1600s until 1967. When my Chinese grandfather married my white American grandmother in 1906, those laws were still in effect throughout the West, which is why my grandparents had to cross five states to legalize their union.

None of that history is new to me. I’ve spent decades writing about my father’s family, even basing my novel Cloud Mountain on this epic marriage. But until a couple years ago, when a distant relative sent me the actual news clippings about their wedding odyssey, I assumed it was a private affair. What shocks me is that racist hatred stalked and hounded them every step of the way. Newspapers from coast to coast tracked their search for a kindly minister, published updates from each stop where they were rebuffed, and lied wildly about their identities.

The truth was that my grandparents met in San Francisco, where my grandfather attended UC Berkeley and edited a pro-democracy newspaper in Chinatown. Though descended from a long line of Imperial officials, he’d dedicated himself to modernizing China on the American model. My grandmother, the daughter of wagon-train pioneers, tutored him in English. When the great San Francisco earthquake struck in 1906, my grandfather saved her life. Within days, they were engaged.

They must have thought the chaos following the earthquake would shield them from public notice while they rode the train east in search of a justice of the peace who would agree to bend the laws against miscegenation. Boy, were they wrong.

By calling my grandmother an heiress, the Denver Post fabricated her status and wealth, and by calling their odyssey an elopement, the headline implied that this Chinese alien was illicitly stealing a prized American gem. Worse, after the desperate couple finally found a cooperative minister in Evanston, Wyoming, Charleston’s News and Courier picked up on a bastardization of my grandfather’s name and stoked the deeper terror: “Miss Dolly Trescott, a white girl, of California, has married a Chinaman whose first name is ‘Sin.’ This should result in something original.”

The headlines might as well have read “From Migration to Mongrelization — Beware!” As one of my grandparents’ “original results,” I’m both thankful and astonished that they had the grit and commitment to persevere. But the hate didn’t stop with their wedding.

Back in San Francisco, the newlyweds faced another form of discrimination. Restrictive real estate covenants commonly prohibited people of color, including “Celestials,” as the Chinese were called in those days, from living in “desirable” neighborhoods.

My wily grandmother had seen this coming. She’d persuaded her new husband to sign the marriage certificate as “Don Luis,” rather than Liu Ch’eng-yu. On paper, he appeared to be Spanish. But for the first year of their marriage, they nevertheless bounced from one apartment to another, each lease terminated when the neighbors complained.

Finally, my grandmother found a flat in Berkeley, near the college campus. Her husband, she told the landlady, was out of town. By the time this Chinese husband with the Spanish name turned up, the lease was signed and sealed and the rent paid a year in advance.

That didn’t stop the downstairs neighbors from launching a whole new Asian hate campaign, demanding that the “Chinese must go.”

My grandmother had had enough. She gave her own press interviews, denouncing her neighbors. The Berkeley Daily pronounced this “Celestial’s Wife Wrathy,” but my grandmother defended her marriage as nobody’s business but her own. She threatened to hire a lawyer. She doubled down on the “heiress” title that the news hounds had given her during her “elopement” and outrageously claimed to be a “blue blood” with roots stretching back to the Puritans. (This strategic move was meant to deflect attention from the fact that she’d been required to surrender her U.S. citizenship in order to marry my grandfather.) She commended the local friends who supported her.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Aimee Liu's MFA Lore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.