Writing in Reverse

Why did Juli Min structure her novel 'Shanghailanders' from the future to the past?

Shanghailanders is interested in the idea of choice, freedom, and what is beyond and within our control. I think a family can be a microcosm of the world, in all of its complex power dynamics and ties and struggles.

Hello Loreates!

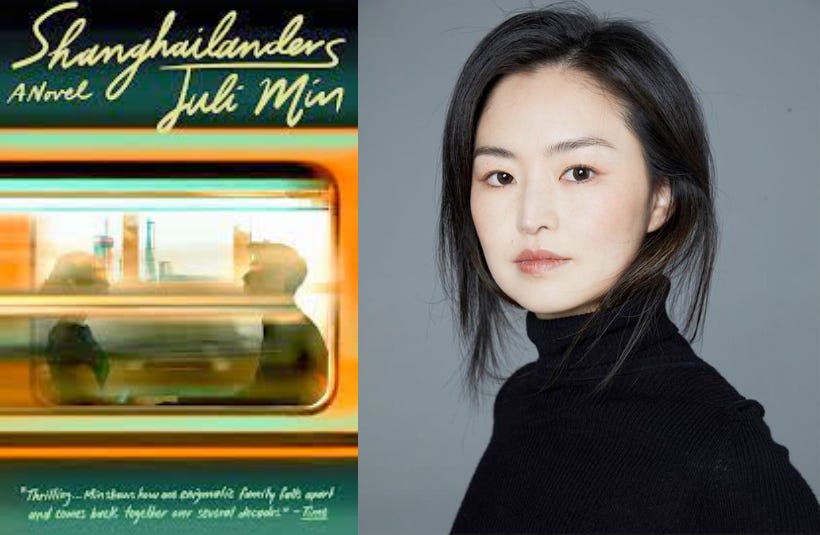

I know some of you are wrestling with structure. [As writers, we’re almost always wrestling with structure!] Well, have you considered structuring your story backwards, starting with a moment in the future and moving unflinchingly in reverse to the origins that launched, and perhaps explain, that future event? It’s a high-wire act for sure, and one that debut novelist Juli Min embraced in Shanghailanders, published last year by Spiegel & Grau and recently released in paperback.

I was delighted when Juli agreed to do both a print and live interview with me, as I did with , another Spiegel & Grau author:

So this is the first of TWO chats I’ll be having with Juli. When we go LIVE on Thursday, August 28, 6pm PT, we’ll be chatting about the logistical challenges of getting published and promoting a new novel in America while living –with a young family– in China. But today, in print, I’d like to dive into the literary complexities of Shanghailanders and the creative process that produced it.

To get you oriented, here’s a thumbnail sketch of the novel from the Los Angeles Times:

Unspooling backward from an imagined 2040 to 2014, this novel shows a Chinese family coping with 21st-century pressures and pleasures across three continents. The Yangs — father Leo, mother Eko and eldest daughters Yumi and Yoko — will interact with the “baby” of the family, Kiko; a long-suffering nanny, or ayi; and a cab driver, in chapters that spiral back to a denouement as sophisticated and affecting as Leo, “a real Shanghai man.”

Paid subscribers, make sure to scroll down to your weekly writing prompt, designed to help you use Juli’s approach to dig deeper into your memoirs and fictional scenes.

An interview with Shanghailanders author Juli Min

Aimee: Welcome to MFA Lore, ,Juli! I’m delighted to have this opportunity to chat with you about your extraordinary novel Shanghailanders. But first, I want to introduce you and your own rather extraordinary background. From what I’ve gleaned online, you were born in Seoul and grew up in New Jersey. You studied creative writing and comparative literature at Harvard and got your MFA from Warren Wilson. You worked as a corporate copywriter for a hedge fund in New York before meeting your husband – a Shanghailander – and moving to Shanghai, where you founded The Shanghai Literary Review. You were also a Lecturer of writing at the Hong Kong University of Science & Technology. You now have two young children, and this book, published by Spiegel & Grau, will be translated into more than five different languages. What did I leave out?

Juli: Thank you, Aimee. And thank you for all you do for the Substack writing community. I’ve been a follower for a while. I was a documentation specialist, which is slightly different from a copywriter - I organized the company wiki, wrote process documents and manuals, etc. It was a great opportunity to write professionally in a way I’d never expected, and a great learning and motivating experience. (Learning that I do not want to work a 9-5 job!) But my heart was always in fiction and stories. Writing has been the main throughline of my life’s story.

Aimee: There are so many unique facets to Shanghailanders that it’s hard to know where to begin this discussion, but let’s start with the basics. The novel opens from the POV of Leo Yang traveling aboard the “maglev” from the airport into Shanghai in the year 2040. Leo is the paterfamilias in the book’s core story. But why did you decide to begin in 2040, and how did you shape your vision of this near future?

Juli: When we think of the future, we often think of something dramatically different - dramatically better or worse than the life we live now. I wanted to push against this “stereotype” of the future. So much changes slowly, or never at all. And with this family, I wanted to investigate how and whether a person, a relationship, or a place ever really changes; and if so, what remains essential at the core. So I decided to work on the scale of decades and generations, to grapple with these ideas, and to also contend with the nonlinear experience of time, expectation, and understanding.

Shanghai is a city that has always had grand ideas of itself and its future, and which has often mythologized its complicated past. I wanted to portray a family that captured different aspects of the city of Shanghai, a city I’ve grown to love. Some elements that I wanted to feature were the speed at which the face of the city changes, its culture of consumption, its social stratification, its cosmopolitanism, its physical beauty, its sexiness…

The maglev is a reconsideration, a modernization of Eileen Chang’s trolley car in her short story “Sealed Off.”

Aimee: I love Eileen Chang! What a brilliant and perfect homage to her and to the nature of change in Shanghai.

Your story moves chronologically and episodically backward in time through the alternating POVs of the Yang family members – including the driver and the nanny. Rather than move back and forth between the story’s present of 2040 and the earlier moments, you chose to follow a straight line, writing in reverse to Leo and Eko’s marriage in 2014. I’ve only seen this done once before, in Fae Myenne Ng’s novel Bone. How and why did you arrive at this structure?

Juli: I’ll have to read that novel, thank you. It’s been so interesting to hear over the past year people telling me about other works of art that have used this same structure. The Sondheim musical “Merrily We Roll Along,” the Seinfeld episode “The Betrayal,” and many more. Ha, in the end, what I thought was pretty original seems to have been done quite a lot!

Part of the decision was a clarity about how I wanted the book to end. I wanted the last chapter to be the wedding of Leo and Eko, a day filled with (mostly) love and happiness. I wanted to end on a note of hope for the couple, who have gone through turbulent decades of marriage. They are, after all, still together after 30 years, and still perhaps in love.

Part of the decision was practical: because there is a big cast of characters, and because so much time passes, I felt a linear regression was simpler, more elegant.

And part of the decision was because of how I wanted the information and backstory of the family members to be revealed for the reader. I was more interested in compounding empathy and understanding, rather than plot per se. The story of a marriage and family disintegrating is quite common; it’s the reason for disintegration that has its many roots deep in the past.

Similarly, we often only learn about the people closest to us through the gradual reveal of their pasts. How much do we know about our parents, for example, and when do they become for us fully fleshed out human beings with secrets, past lives not lived, shames, joys, desires? It takes time (the linear progression of moving forward, aging, maturing, pages flipping, episodes divulged) to see a person clearly, if that is ever even possible.

Aimee: This story is intensely global. It opens with the family scattering from China to America and France. Leo’s wife Eko is Japanese, raised in Paris, where Leo met her. The daughters go to school in Boston. The fiction’s ease of travel across borders seems very optimistic. I’ll admit to feeling a bit of cognitive dissonance reading it against the Trumpian reality of 2025. But I assume the novel reflects your own experience, and maybe your view of the future from Shanghai? Is that view changing with current events, as ours is – drastically – here in America?

Juli: What forces limit human choice, and what forces allow us to break free? That is a question I was considering constantly during 2020-2022 during the writing of this book. (Some of it during Shanghai Covid lockdown, when I could not open my front door for weeks on end.) This is a very privileged family - they are gorgeous, smart, multilingual, wealthy. Their set of privileges and powers allow them to float above some of the realities of life that others get stuck in. It is a truth about privilege and money - that it makes the world a smaller place, provides access and escape. In 2025 that is still true, but it has been true throughout human history.

In the novel, the Yangs’ private driver has never left Shanghai. His life is much more circumscribed, a closed loop. For the chapter narrated by the nanny, her life is completely dictated and altered by the choices of her employers - so then, where can she and where does she assert her agency? These were questions I wanted to explore.

With regard to my view of the future from where I live, I will confess to suffering from constant low grade anxiety, not unlike Leo. At the same time, when portraying Leo’s anxiety and his extreme attempts to safeguard his family and his life from risk, I felt it was important that his predicted apocalypse never occurs in the span of the novel. No death, no doomsday, no divorce.

Aimee: At its heart, Shanghailanders seems to me to be wrestling with the question of destiny vs consequence. Do we make our future, or do we fall into it? Many of the chapters seem to highlight critical moments in the family’s life when different choices might have changed the course of their history – and their dynamics. There is also the essential question of belonging as each character struggles to secure a sense of home and trust and identity in a world whose contours are constantly changing around them. When you write, do themes like these emerge gradually out of the story, or do you start with them, so that they guide you into the story?

Juli: This book started as an exercise in capturing elements of contemporary Shanghai. I was thinking along the lines of Dubliners, Winesburg Ohio, Olive Kitteridge - how I could paint a picture of a city through its inhabitants. So this project originated quite top down - themes moving into characters.

But of course those characters took on lives of their own, voices, and connections with family and others. Once I have a line or a character or an image in my head (like the image of an illegal drag race through Shanghai’s Bund) I start drafting and just let things progress naturally. That is to say, I don’t structure scenes or chapters or plot much before writing.

But of course there are small decisions being made all the time, and I do have overarching ideas and connections at the forefront when drafting. For example, when writing about Yoko’s abortion in Paris, I knew that I wanted there to be links with her mother’s abortion long ago, and with her grandmother’s decision to leave her grandfather. And that all of those moments were connected to a larger idea of choice - life-altering choice.

You’re right that Shanghailanders is interested in the idea of choice, freedom, and what is beyond and within our control. I think a family can be a microcosm of the world, in all of its complex power dynamics and ties and struggles.

Aimee: I was very intrigued by Eko’s claim to fame, which is hand embroidery that depicts the botanical world. It presents a meaningful contrast to her husband’s lucrative career as an engineer and architect, especially since it arguably makes her more famous than he is in the end. Where did the idea for Eko’s embroidery come from?

Juli: I follow Yumiko Higuchi online, and I love her work with nature embroidery. So the idea of becoming Insta-famous doing something so specific came from reality.

A lot of the book is concerned with the power and influence of beauty. Eko has been interested in aesthetics her whole life. She and her mother hand made clothing when living together in Paris. They worshiped at the altar of fashion. Eko studied to be an interior designer. Later in life, she designed family properties. I wanted her to, on some level, always be the same.

Eko’s character as a middle-aged woman is quiet, elegant, and a little bit retro. Compare that to her husband, who is louder, more confident, and more structured. I felt the scale and quality of their works represented who they are. And I imagined Eko, who is isolated in various ways in the concrete metropolis of Shanghai, completing her embroidery work by herself, sort of finding the right way to feed her soul. Embroidery brings her solace, independence, community, and also connection to her Japanese heritage.

Aimee: Finally, I believe you started this project with your MFA thesis work at Warren Wilson? Did it start as linked short stories? Could you talk a bit about the role that your MFA played in getting this novel off the ground?

Juli: Yes, it did start off as linked short stories. When I decided on the backwards structure, I could then conceive of it more like a novel, with a linear progression that tied things together, albeit still loosely. I wrote about half of the chapters / stories during my MFA, and then after graduation, I gave myself a deadline of three months to write more and submit to agents. I didn’t want to lose the momentum I’d gained; and it had always been my goal to publish.

My MFA was instrumental to the making of this book. I think you can feel the sense of play and experimentation throughout the novel; that was me trying out different craft ideas and different styles of writing throughout my studies. That was me being influenced by so much reading and analysis and lectures and workshops. That was me trying to condense the richness of inspiration I felt during three years into a project. That was me learning how to sit down every day and fill pages and complete assignments.

Because my MFA was a distance/virtual MFA, it really helped teach me that intensive writing and creativity can take place in the spaces and structures of daily life. I wasn’t off on a campus isolated from the world for two years. I was having kids, and I was working as a magazine editor. My life didn’t stop so that I could study and write books. I made time for art in the existing reality of my life. That was one of the best things I took away from the MFA.

Coming Live Attractions free @ MFA Lore:

1. Well Published: LitMags!

Live with Sub Club Creative Director , Thursday, July 24, 1pm PT/4pmET:

2. Authors Unfiltered !

Traditional publishing insights from the trenches Live with and :

August 12, 2025 (Tues), 4:00 pm PT: Authors Unfiltered on Niche Writing

September 23, 2025 (Tues), 3:00 pm PT: Authors Unfiltered on Author Platforms

3. Well Published: Publishing Globally

Live with debut novelist Juli Min, who lives in Shanghai and has a US publisher, Thursday, August 28, 6pm PT.

4. Well Published: Book publicity

Live with book publicist extraordinaire

, Thursday, September 18, 12 noon PT.Loreate Salons for Paid Subscribers are now bimonthly!

By popular demand of our Zoom Loreates, we’re now going to gather online every two months on the third Saturday. This day and time seem to work for everyone from Hawaii to Switzerland, so…

Our next gathering is Saturday, July 19 at 10amPT!

All paid subscribers are welcome. As we get to know each other, these gatherings will be less meet-and-greet and more discussion of the thorny issues bedeviling our collective writing life. Consider this online space our Loreate Salon.

Would you like an MFA-level response to your work?

Becoming a Premium Member of the MFA Lore community will entitle you to Aimee’s written feedback on your query and up to 5 pages (1250 words) of your creative work. Your “Take 5 Packet Letter” will highlight both the Strengths and the Opportunities in your work, helping you determine whether it’s time to “press send” to agents or to reorient your revision. Price will go up next month, so subscribe or upgrade today.

Your Weekly Writing Prompt

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to MFA Lore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.