Letters of Consolation and Estrangement

Grandfathers I wish I could have known

In an unmarked manila envelope that smells of mildew, I discover letters from opposite sides of my family’s Chinese-American divide. One is from my paternal great-grandfather Dr. W. Herbert Trescott, the other from Doc’s son-in-law, my grandfather Liu Chengyu. These two consolation notes are emblematic of the divisions within families that so often occur as a result of what I’ve come to call migration estrangement.

Especially in the last century, when one generation set sail for a foreign country, many lost forever the family members left behind. In my family, this estrangement began even before geographic migration, with the crossing of cultural boundaries.

Lost in America

The note from Doc Trescott, penned on stationery labeled “Naturopath Physician, nervous and chronic diseases,” is addressed to his daughter, my grandmother Dolly, in Berkeley, California. It’s dated March 1911, five years into Dolly’s marriage to my paternal grandfather, Liu Chengyu, a.k.a. “Don Luis”.

“Don,” my grandfather, edited San Francisco Chinatown’s revolutionary newspaper Ta Tung Daily and was a protégé of Dr. Sun Yatsen (now recognized as the Father of Modern China). When Sun came to America, Don organized audiences of hua chiao — journeymen and merchants of the Chinese diaspora — to hear him speak of the great democratic revolution happening back home.

In 1911, Dr. Sun and my grandfather worked their way north to Victoria, Canada, and through the nearby mining and timber towns, anywhere Chinese had numbers. They sold $70,000 worth of Hong Kong bonds to fund the next rebel action. All went well until Don and Sun sailed back from Vancouver with a trunk containing $500 in gold donations to the cause. The gold was to be banked in Frisco, but as Papa and Dr. Sun stood waiting on the dock, one of the stevedores “accidentally” slipped on the gangway, casting the chest into the bay (presumably to be recovered on his own watch).

In the aftermath of this debacle, my grandmother must have written to her father for help reclaiming the money. Not that Doc had any strings to pull. A wagon-train pioneer originally from Boston, he’d failed at cattle ranching and gold mining, and was now eking out a living as a naturopath in Los Angeles. This letter was his curt reply:

Dear Dolly,

I received your letter this morning and I think a spanking would do you good. The last I heard from you, you were sick in bed in Frisco. I wrote there and got no reply. I did not know if you were dead or what. You can write fast enough when you want assistance, but not otherwise.

Don seems to be either out of luck or negligent, I do not know which, for he gets it good and hard from all directions you can bet. I would find a way to get them to cough up that $500. If he does not assert himself more he will be always an easy mark. He is no more out of the frying pan than he is in the fire. I guess his seven years of hard luck must be soon over and I guess his hard luck must have commenced with you. Well, tell him I am glad he returned safely and that it was not him instead of the box that went overboard (there was some luck there for him, or was it not).

Love to all,

Dad

Out of luck, indeed. The harshness of Doc’s tone speaks of his own hurt and doubtless guilt over the estrangement from his headstrong daughter, which began in her infancy, when Dolly’s mother died and Doc left her to be raised by trailmates while he futilely sought his fortune. The gulf between them only widened when she grew up and married my Chinese grandfather.

And yet I’m struck by the mildness of Doc Trescott’s criticism of his Chinese son-in-law. While despairing of Don’s bad luck and negligence, he seems to reserve the real blame for his daughter.

“I guess his hard luck must have commenced with you.” Ouch! Is this a veiled dig at Dolly for marrying across the racial divide? How else could she be responsible for her husband’s mishap?

So much for any “assistance” in covering the lost gold. Still, my great-grandfather’s sympathy for this star-crossed couple ultimately transcends his own injured feelings. “I am glad he returned safely.” Many other white pioneer father-in-laws would have taken a less charitable tack than to close this note with, “love to all.”

There’s no way of knowing if the money was ever repaid, but with or without it, Dr. Sun’s campaign to overthrow China’s Manchu rulers soon succeeded. Just eight months after receiving Doc’s note, Dolly packed up her three-year-old daughter Blossom and sailed to join Don in Shanghai, where my father was born four months later.

Doc would never see his daughter and son-in-law or any of their children again. He couldn’t have known that when he sent his scolding in 1911, but he clearly sensed Dolly slipping away.

That estrangement was common ground he would come to share with his Chinese son-in-law.

Lost in China

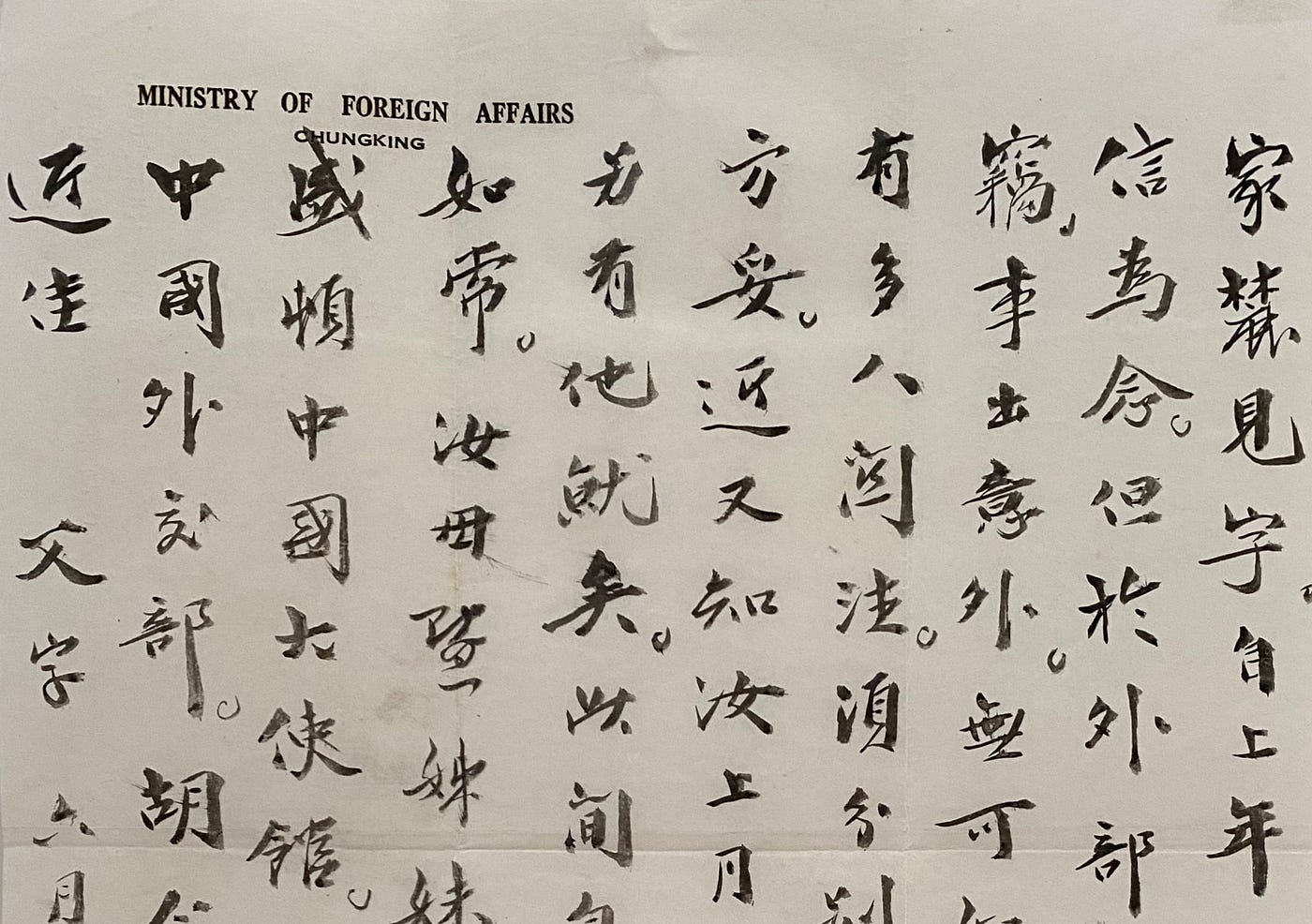

Fast forward 32 years to June 30, 1943, the date on the second note in my late father’s mildewed envelope. The calligraphy here bears no resemblance to Doc’s terse penmanship. This hurried brushwork addresses my father in Chinese. Nevertheless, the contents of this message, too, refer to a potentially catastrophic mishap, while speaking to an even larger inter-generational loss looming on the horizon.

Unable to read Chinese, I’ve had to have my grandfather’s letter translated. That in itself reflects the familial estrangement embedded in these lines:

To Jialu:

You have not written a letter to let me know your recent situation since you left last year. I was informed from outside sources that you were robbed on your way back. It happened in a sudden and there were nothing you could do about it. People who went with you sent me letters separately to let me know about your situation, so please thank them for that. Recently, I heard that you resign [from your job] last month. It’s probably because you’ve found another good position. (You were there long time and it was all right.)

Ask to see if you are all right recently.

Your Father

The robbery that my grandfather refers to occurred in the midst of World War II. Having lived in America for ten years, attending USC and working at the Chinese Consulate in Los Angeles, my dad had finally gotten funding in 1941 to return to China as a documentary filmmaker. He spent six months shooting footage of the Red Cross’s war efforts on behalf of Chinese civilians. He worked in battlefield hospitals and makeshift clinics. He also was reunited with his father, then an official in China’s wartime capital, Chungking. But in March of 1942, Dad left China by military transport, flying over The Hump from Kunming to an airfield in Assam, and on to Calcutta. He made the tragic mistake of checking his film canisters — the entire body of his work — in the DC-3’s cargo hold. By the time he debarked in Calcutta, the film was gone: It happened in a sudden and there were nothing you could do about it.

Dad never told me what happened when he finally arrived back in the States empty handed. “It was nothing,” he would insist. “They were just some Red Cross training films.” Even decades later, he couldn’t admit the magnitude of his loss. Not just the waste of his effort and career prospects as a filmmaker, but also the final link that those films represented to his father. In 1949 the Communists would pull down the Bamboo Curtain, cutting off all contact between China and America. It would be decades before the family here learned that my grandfather had died in Wuchang in 1953.

Dad acknowledged the robbery but not his father’s attempt at consolation. I only discovered this letter after Dad himself was gone, so I can’t account for the blackout that followed his loss. “It’s probably because you’ve found another good position,” my grandfather wistfully rationalizes. Already he seems to concede that the breach between him and his son has widened beyond mending.

Left behind

When I place my grandfathers’ letters side by side, I’m stunned by their parallels.

- You have not written a letter to let me know your recent situation since you left last year.

- I did not know if you were dead or what.

Two hurt and worried fathers left behind. Worlds and eras apart, both struggled in their impotent ways to reconnect with children who’d slid so far out of their grasp they could never be reclaimed. Children whose mishaps had provided one last excuse for counsel and connection but who were destined to turn away and never see their fathers again.

Perhaps I’m sentimentalizing my dead grandfathers, but different as their approaches may be, both men speak to me of the yearning and regret that permeate families riven by migration.

It happened in a sudden and there were nothing you could do about it.

Like waking to the realization that your children are about to vanish forever across the ocean, and you have no choice but to let them go.

What a riveting essay! And what a fascinating parallel between the two fathers as they expressed how they missed their respective child. I read both with a pang in my heart as the sentiment mirrored my own father's during the long periods we were living in different countries and were estranged. Your great grandfather's tone was really harsh and gave the impression of a man steeped in misogyny (which was probably true of all men at that time period? Sorry about making this assumption) -- e.g. giving Dolly a spanking and blaming the woman for choosing the wrong man (something my mom used to do!).

I am very curious about the original Chinese letter written by your grandfather to your dad. The photo here shows a cropped part of the letter. Would you mind sharing the entirety of it so I can study the content and the penmanship? The sentence structure and the punctuation are different from the modern Chinese language, but typical of the pre-Communist era.

Beautiful essay. Connecting the universal experiences of parents and children with your own unique and remarkable family.