Memories of a “Cloud Mountain” Boyhood: Lushan, China, 1947

A rare view of pre-Communist China after WWII, with Ian Grant

Hi Everyone,

My next two posts are going to shift to the East-West Legacy side of this publication. I’ll be back next week with more MFA Lore, but I thought it worth taking a break (especially given this week’s political nightmare) to share

’s extraordinary boy’s-eye view of China after WWII and through the Communist takeover. And for me, this interview is not disconnected from writing, since the setting for Ian’s memories is the very place my historical novel Cloud Mountain was named for: Lushan (Mt. Lu) in Jiangxi Province.When I was gathering family stories from my father as background for Cloud Mountain, Dad described Lushan, where he summered as a boy, as “a kind of paradise for our family.” This had as much to do with the resort’s social environment as with its natural beauty and idyllic climate. The town of Kuling, today known as Guling, had been developed on Lushan in 1916 by and for Americans, who were far more welcoming than British or French to Chinese and mixed-race families like mine.

My Chinese grandfather and American grandmother had endured brutal prejudice in San Francisco at the start of their marriage, and in European-controlled Shanghai they had to navigate the segregation of Chinese and Eurasians. But on Lushan, they felt free. The kids socialized with the Americans and Russians who summered there. And in the early 1930s my grandparents built a cottage in Lulin, the next valley up from Kuling.

My father’s photographs of Lushan stoked my imagination, and I set much of my novel there. Though I didn’t have a chance to visit before Cloud Mountain was published, I developed a strong sense of the place, in part, from the evocative memoirs of my late friend John Espey, who attended Kuling American School, a boarding school in Kuling for the children of U.S. expats.

Then, nine years after Cloud Mountain’s release, I discovered that the Kuling American School Association (KASA) was planning a reunion trip back to Kuling in the spring of 2007. Though no one in my family ever attended the Kuling School, KASA graciously allowed my husband and me to join the tour, and that’s how I met Ian Grant (fourth from left in photo below).

Ian’s parents were Canadians with the China Inland Mission [CIM], formed in 1865 by Britisher Hudson Taylor. They were stationed in Hebei province, but due to social unrest, in July 1940 they had been moved to Chefoo, today a district within the city of Yantai but then a Treaty Port on the north shore of Shandong province, where Ian was born later that year. The Mission had established a boarding school at Chefoo for children of their missionaries, which Ian would attend. But first, his family returned to Canada, where they waited out WWII before returning to China in 1946. But then China’s civil war forced the Chefoo School to relocate to Kuling, which is how Ian came to be part of the KASA tour.

If that all sounds like a saga, it is! Which is why I was delighted when Ian agreed to let me interview him about his East-West Legacy.

I’m going to present this lengthy interview in two parts. In Part One, we’ll talk about Ian’s initial childhood sense of China and Kuling. In Part Two, he’ll tell us about his experience leaving China after the Communist takeover, when he was 10.

Become a Paid Subscriber of MFA Lore now! Just $42 for a whole year of full access. Birthday Special ends July 22!

Interview with Ian Grant

Aimee: I’m excited to do this interview with you, Ian! Kuling was an important place for my family, and I can think of few people who knew it better than you. Could you start by telling us how the Chefoo School wound up in Kuling?

Ian: Following the Japanese withdrawal from China after WWII, the Communists established themselves in the rural areas of northeast China, and this included Chefoo. They did not permit Western businesses, missionary activities, or institutions to return to these areas, and this left the CIM in search of an alternative site for the Chefoo School.

Fortunately, they were able to acquire the empty campus of the Kuling American School, which had not reopened after the War. The Chefoo School was moved there late in 1947, and they were ready to commence classes when children returned to school following Christmas vacation at their respective parents’ mission stations. My brother and I happily arrived near the end of January 1948, when I was seven years old.

Aimee: What an odyssey! War, migration, displacement, homecoming, and then that sojourn up the Thousand Steps to Lushan. What do you remember feeling and seeing during your first journey to Kuling? Who escorted you? Were you used to being apart from your parents already by age seven?

Ian: In China the missionary practice was to have a long winter break, so children could spend this time with their families at their mission stations, and only two to three weeks off in the middle of the summer, when most students, unless their parents lived quite close by, would remain at school. My general pattern was to be homesick for a week or two when we were separated, but I gradually was able to focus on the life around me. I did not feel sorry for myself because I knew all the other children were experiencing the same thing. I was happy, however, that my father escorted our contingent back to school.

When we got to Jiujiang, on the Yangtze River, we were taken by truck to the foot of the Lushan mountains. In those days there were no motor roads in Lushan, so either we walked up the mountain path, or, if small like me, we were excited to be carried in a sedan chair.

Like so many other events I experienced as a child in China, this was a new experience, and I enjoyed the long climb up the mountain. Especially in the early stages it could be very steep, and at one point there are so many continuous steps that it acquired the name One Thousand Steps. In China ‘many’ is often described by thousands, such as ten thousand years, or one thousand steps, but I don’t remember anyone at our school claiming that they had actually counted them.

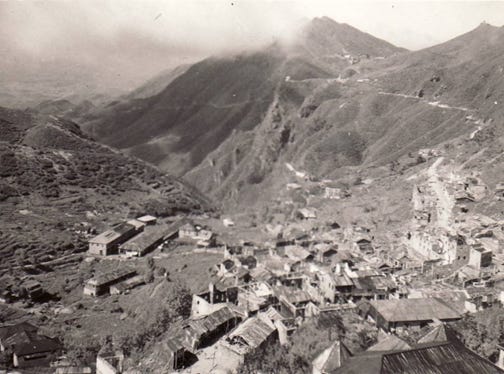

Finally, we were at the top of the mountain and entered the Kuling Valley through a Chinese Village that was known to us as The Gap. From here we continued on till we reached our new school location.

I don’t remember arriving at the school, being assigned a bedroom and bed, nor having anything to eat. But I do remember being told we were going to join some other children for a walk. I remember meeting these children coming down a pathway and being suddenly enthralled by the beauty of the mountains and the pathways, and all the children seemed so cheerful. I knew I was going to be happy here.

Aimee: Your memories are so poignant for me. Before the war, my family built their summer home in Lulin, the valley adjacent to Kuling. There they could escape the grotesque prejudice of the British Shanghailanders against mixed marriages. Lulin was also called Russian Valley, I believe, since many Russians lived there.

Ian: My understanding is that the people who built homes in Lulin were Westerners other than the British and Americans, who monopolized Kuling Valley, along with a few Chinese elites such Chiang Kai-shek. There were quite a few Chinese houses in Lulin Valley also.

Aimee: But in 1939, during the war, the Japanese bombed Lulin to smithereens, even though they left Kuling relatively unscathed (probably planning to occupy the gorgeous western villas there if they’d won the war).

Ian: My understanding was that the Japanese purposely did not bomb Kuling because they did not want to anger the Americans and British, who they were not yet at war with. Fortunately, the bombing was relatively brief. After Pearl Harbor the Japanese took Kuling over.

Aimee: My grandparents’ home was obliterated. But when you arrived in 1947, my grandfather still lived in China, and I often wonder if he returned to Kuling around that time. Maybe he saw you when you were out playing!

Ian: We frequently walked through Russian Valley on our way to the Three Trees, and the Three Graces pool (Black Diamond Pool).

Aimee: Did you notice any evidence of the war around you?

Ian: As children, we knew nothing about Lulin valley other than what we found, and in general we walked and played there as anywhere else. I don’t recall anyone expressing wonderment that there were no buildings. We simply took life as we were experiencing it.

Aimee: What was the general mood of China toward foreigners at that time?

Ian: I did not perceive that the Chinese resented us being there, but children were another matter. It was normal for children to follow us, call us names, and even throw stones at us, not to hit us, but to scare us. We always ignored them and were not fearful of harm. I don’t remember the parents of these children ordering them to stop, but neither did the parents behave in this unfriendly way. I think, for the most part, the children just did this for sport. Foreigners were often not often seen, so we were a novelty for them.

Aimee: How much did you understand about the history between China and the West?

Ian: It has been in my adult years, especially the last 20 years, that I’ve come to appreciate how badly Western countries exploited and humiliated the Chinese.

Westerners were in many ways not welcome in China in those years because we were seen as the instigators in what China, to this day, considers the 100 years of humiliation. Throughout the nineteenth century, Britain, followed by the French, Germans, Portuguese, Americans, and then the Japanese relentlessly forced themselves on China so that they could have free access to their markets. This resulted in outright war on China on two occasions, which led to extraterritoriality, meaning that Westerners could not be tried in a Chinese court. ‘Treaty ports’ were established where Western countries could trade freely, and Westerners were permitted to travel to and live anywhere they could in China. This was, indeed, the impetus for the missionary movement that commenced shortly after the Treaty of Peking in 1860.

Aimee: Despite all that bad blood, were there any Chinese people you grew close to in China? I ask because I have photographs of my father’s friends and the people who helped raise him. Dad’s surrogate father was a wonderful man named Yen, who vanished into the ether along with my grandfather after the “Bamboo Curtain” fell in 1949.

Ian: At boarding school, we had no real opportunity to interact with the Chinese. Children who did, like my younger brother, were too young yet to go to school; at their parents’ mission stations the only children to play with were Chinese. My brother’s friends were the landlord's sons in an adjacent building. They became constant companions, so he became fluent in Chinese.

I have often wondered what happened to my parent’s landlord and his family in Kunming. As soon after the Communists took over, most landlords were persecuted, lost their land, and many were executed.

Aimee: I, too, wonder about those times. My grandfather remained in China, with no way to escape. He’d served in the Nationalist government, but he’d also been a close friend of Sun Yat-sen, so he may have been spared, but for decades we had no idea even whether he was dead or alive. It wasn’t until 1995 that I learned he’d died in 1953 in his hometown of Wuchang, but we probably will never know the circumstances of his final years.

You were lucky to get out after the takeover, Ian. In Part Two of this interview, we’ll talk about that!

Fascinating interview. As a history buff, I enjoyed imagining the China of that time through Ian’s eyes.

This was so fascinating to read. China has gone through so much in the last century, that there's never a shortage of historical details to fill in my knowledge gap. This is certainly one such gap that I had no knowledge of, particularly the parts about foreigners living and enjoying life in China in between the wars. I had never heard of the Russian village, for example, and what Lushan meant for both the Chinese people and foreigners living there. I also really enjoy the photos you've included in this interview, offering a very rare glimpse of parts of China that I've never seen, neither in history books nor in real life.